In the middle of the year 2017, the Czech Philharmonic was in mourning over the death of Jiří Bělohlávek, the orchestra’s legendary chief conductor. Five years earlier he had returned from London, where he was the conductor of the BBC Symphony Orchestra, and started a revolution in Prague that began to move the Czech Philharmonic back to its place among the world’s few top orchestras.

The Green Room at the Rudolfinum, an opulent “office” with a sofa, a shiny piano, and a spacious wardrobe, feels empty. The orchestra’s management, artistic council, and principal players held a meeting to debate over whom to approach as Maestro Bělohlávek’s replacement. Semyon Bychkov, they all agreed. It was a bold choice. At the time, Bychkov had been persistent in refusing offers of posts as chief conductor with truly first-class ensembles for seven years, including the aforementioned BBC Symphony Orchestra. He no longer wished to be tied down.

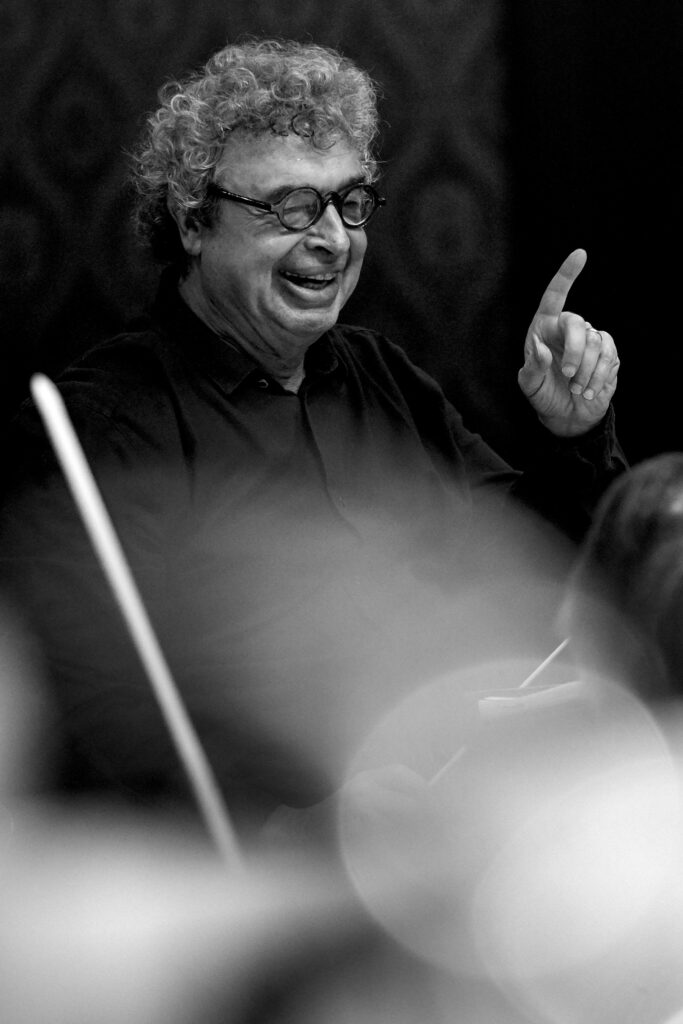

“I said something to the effect that working with him is great, that we appreciate his attitude towards us, and that we feel respect for him”, he recalls. “And that we would like him to be our…well, I just put it somehow in a personal way…we want him to be a father to us. Our daddy.” Semyon is obviously moved, and he later reveals to journalists that he had never heard such a nice speech before. He takes some time to think it over, but before long he confirms that from the following season he would become the “daddy” of the Czech Philharmonic.

Leningrad, 1964

The winters are long and freezing in Leningrad, and since water weaves its way through the whole city the cold gets to you mainly because of the dampness. Anyone not born there has trouble with the cold weather; this is still true today, although Leningrad is once again called Saint Petersburg (thank goodness).

On yet another cold evening, Semyon is huddled in his coat. He is twelve years old and is studying at the Glinka Choral School, an elite music school for talented boys from all around the Soviet Union. During the admissions process, five hundred boys applied, and they selected twenty. Semyon is studying choral conducting, and the professors sometimes call him “Little Pushkin” because of his curly hair.

Little Pushkin, although truly not very big, also plays volleyball for the team Dynamo Leningrad, and he has so much élan and desire to win that the coach almost never takes him out of a game, even when it doesn’t happen to be Semyon’s day. On that freezing winter evening, something happens that changes the boy’s life: as they walk together through the darkened streets, the boy’s father begins to explain to him the reality of living in the USSR.

He says: “There is no truth to what they are telling us.”

He says: “The whole Soviet Union is based on a lie.”

Eight years earlier, in February 1956, at the 20th Congress of the Communist Party of the USSR, Nikita Khrushchev gave a legendary speech condemning Joseph Stalin’s cult of personality. From then on, people in the country could breathe a bit more easily, but even so, Semyon’s father could have been thrown in prison immediately for saying something like that.

But he was brave. He wanted his son to understand the system he was living under. And in those days, most parents were trying hard to do the opposite: political debates took place at night at the kitchen table, cautiously, with lowered voices. After all no one wanted their child to let something awkward slip in front of a loyal communist teacher… Semyon understood his father’s words, and he committed them deeply to his memory. Eleven years later he departed from the USSR. But we will get around to that.

Leningrad, 1957

The House of Scientists stands beside the Neva River in the sumptuous Vladimir Palace, built in the 19th century. The prettiest view of the palace is from the Peter and Paul Fortress directly across from it. Semyon is five years old the first time he comes here. The family had access to the club – his father was a scientist who studied psychology and the electrophysiology of the brain. At the time he was working as an army researcher.

The House of Scientists stands beside the Neva River in the sumptuous Vladimir Palace, built in the 19th century. The prettiest view of the palace is from the Peter and Paul Fortress directly across from it. Semyon is five years old the first time he comes here. The family had access to the club – his father was a scientist who studied psychology and the electrophysiology of the brain. At the time he was working as an army researcher.

Among those working at the House of Scientists was Lina Fyodorovna Anikina Stepanova, a graduate of the Warsaw Conservatoire from the era before the revolution. She gave piano lessons, and it was to her that Semyon was taken by his mother, who herself played piano in her childhood. Lina Fyodorovna was to judge whether Semyon had musical talent. He did. Perfect pitch and a strong sense of rhythm, said the professor. For the next two years, Semyon went to her for lessons. At his first concert, he played a sonata by Muzio Clementi. He was six years old and not nervous in the least. On the evening before the concert, Lina Fyodorovna taught him how to walk on stage and how to bow. Later, Semyon played Grieg’s March of the Trolls. “Do you think there is such a thing as trolls?”, asked the professor. “Of course!” Semyon had no doubt in the least that trolls existed. Lina Fyodorovna recommended to his parents that their son apply to the Glinka Choral School.

Leningrad, 1960-1970

All the pupils at the Glinka school sang in the choir, even when their voices were breaking. The chief conductor Fyodor Mikhailovich Kozlov made a huge impression on Semyon, so the 8-year-old boy knew right away what he wanted to be. At home he began waving an improvised baton in front of a mirror (what else?) to music that was playing on a phonograph or that was simply in Semyon’s head.

For Little Pushkin, the years that followed were filled with nothing but music and volleyball. Semyon would go back and forth from team practices to his piano lessons, and later he began attending concerts in the evenings, and he would arrive home just before midnight. It was clear, however, that once the moment of decision arrived, volleyball would be put aside.

Semyon graduated from the Glinka School with honours. Assuming that he went there to study choral conducting, this automatically guaranteed him admission to the prestigious Leningrad Conservatoire..

But Semyon did not want to conduct choirs. He wanted to be an orchestral conductor. To study orchestral conducting, he had to pass an entrance exam, and that was terribly risky. If he did not succeed, he would be conscripted into the army. There were 78 applicants, and some of them were old enough to be Semyon’s father. Some students at the conservatoire were applying for the third, even the fifth time… In addition, that year (1970) only one applicant (!) was to be accepted. Now ask yourself – why should they choose this 17-year-old with his unkempt hair in particular? A waif like that really shouldn’t even be applying! You have to be a mature person to study orchestral conducting, and successful in other fields, like composing or playing an instrument. At least, that was the opinion of the grey-haired professors. But that boy with the unkempt hair really wanted to go to the conservatoire. And not just the conservatoire – he wanted to go straight to Ilya Musin, a phenomenal conductor and probably the best teacher in the USSR at the time. Those admission exams are hard – ridiculously hard. The applicants listen to a phonograph recording and have to write out the musical notation just from listening. Or a score is open to a random page, and they have to identify the work.

“That is Beethoven’s Symphony No. 7.” “Right. Now tell us, in which of Beethoven’s symphonies and where did he first use trombones…” Semyon was nervous and felt like he was failing in one round after another. But to his surprise, he made it to the last round together with seven other “survivors”. The final task was to conduct a symphony orchestra – a real symphony orchestra. Semyon had never conducted a symphony orchestra before. “Look,” said his colleagues, the ones old enough to be his father, “on the conductor’s podium, you will hear something completely different from what you are used to hearing in the hall. You won’t understand it, and it won’t be clear to you who is playing what. But don’t worry about that. Just conduct.” Semyon entered the hall, went to the podium, and raised his baton.

And something amazing happened. The orchestra played, and the boy heard absolutely everything. He knew exactly how it should sound. He was in the right place. That year, he was the only student accepted as an orchestral conducting student at the Leningrad Conservatoire. That evening, he and three friends drank three litres of vodka and a bottle of sweet Moldavian wine.

Vienna, 1975

Semyon was aimlessly – and blissfully – strolling through the streets of Vienna. He had no map – what would he need one for, anyway? He passed a market where bananas were being sold at a stand. Real bananas, just like that, as if real bananas were something commonplace. And commonplace they are unless you are an emigrant from the Soviet Union who, at the age of 23, had seen bananas possibly three times in his life, but probably only twice. Semyon put down his carry-on bag and bought a whole bunch.

He immediately ran to the adjacent park, as if he feared that were he not to eat the bananas right away, they would disappear. “About halfway through banana number seven, I realised that I had forgotten my carry-on bag at the stand.” Semyon’s heart stopped – after all, his whole life was in there: his birth certificate, his certificate of marriage (Semyon married for the first time in 1973, and his wife was with him in Vienna), his transcripts from the conservatoire (he was expelled in the middle of his last year when he applied for permission to emigrate), and his diploma for first prize at the Rachmaninoff Conducting Competition. The horrified Soviet emigrant hurried back to the stand. The bag was lying exactly where he had put it down. Of course.

Vienna, 1975

The feeling of freedom is intoxicating, even if one does not know what to expect. As he wandered around Vienna, Semyon’s thoughts turned to his father. After the Six-Day War between Israel and its Arab neighbours (1967), Moscow broke off diplomatic relations with the Jewish state, and anti-Semitism, ever present in the USSR, seemed to be on a rampage. Semyon’s father, who had just left the army, was looking for work, but without success. The directors of the research institutes he visited for interviews were his classmates and friends. They could not hire him because he was a Jew. Semyon himself was not yet feeling the anti-Semitism, apart from some sporadic verbal attacks on the street. He was living in an artistic and intellectual bubble. But he would soon get his turn.

In addition, since that walk through freezing Leningrad in the winter of 1964, Little Pushkin had been harbouring a lasting hatred of the Soviet system. He began listening to Voice of America, although that was illegal, of course. The Soviets tried with all their might to jam the broadcasts, but they succeeded only partially. And Semyon, like many of his acquaintances, finally arrived at the definitive conviction that he had to leave. Nothing good awaited him in the Soviet Union. So, he and his wife requested permission to emigrate. He was immediately expelled from the conservatoire, and his wife had to leave her job. So, they waited. The outcome was extremely uncertain; the emigration authorities had turned down so many families!

The local KGB called in the young married couple on a Friday afternoon. “Friday afternoon means you’ll be turned down for sure; that’s just how it goes,” the thought flashed through Semyon’s mind. But wonder of wonders: “Your request for emigration has been reviewed carefully… and approved.” In shock, all Semyon managed to say was: “And what am I supposed to do now?” Even the stern KGB agent burst out laughing. Three weeks later, Semyon and his wife landed in Vienna. That same year, they settled in the USA. Semyon’s mother and brother came in 1976. His father was not allowed to leave the USSR until under Mikhail Gorbachov. In 1987.

Leningrad, 1941

About his mother, Semyon says: “Like a whole generation, she too lived a life of a kind we can scarcely imagine today.” She was born in Leningrad, and her father was a physician, a noted lung specialist. And also an amateur composer. “Yes, that’s where it was coming from. And his father, my great-grandfather, was a conductor in Odessa, and for a long time I didn’t know about it.” His mother was born in 1924. “What does that mean? That she was 17 in 1941. And in the USSR, at age 17 you leave school and go to university. On Saturday, 21 June 1941, everyone born in 1924 all over the Soviet Union was attending a graduation ball. They were celebrating their adulthood. They could drink, smoke, marry, go to university, or go to work. They all had their own dreams. Up north, they have the white nights, so the party went late, with dancing on the banks of the Neva River until the morning hours.”

Nobody probably even knew what time it was when the news broke that Operation Barbarossa had begun. Hitler’s Germany attacked the USSR on 22 June 1941. Semyon’s mother spent the entire siege of Leningrad, all 900 days, in the city. She was not evacuated. Everything was in a state of chaos and ruin; nothing was working. The daily ration of bread was 125 grams per person.

The sirens were wailing again as another bombardment began, and people ran for their cellars. A bomb fell on the building where his mother was hiding underground. It penetrated the whole building down to the cellar, but it did not explode. “Divine intervention.”

After the war, his mother finished her study of English and French and became a teacher. She married and had two sons. Her husband was sent to Kazakhstan by the army, and the mother stayed in Leningrad with the boys, mainly so Semyon would not have to leave the Glinka Choral School. She worked and raised her sons, but she never complained; she didn’t have time for it.

USA, Europe, 1975-2017

In America Semyon completed his studies, graduating from New York’s Mannes School of Music. He conducted in Michigan and New York, making his New York debut in 1981 with the opera Carmen. Two years later, he became an American citizen.

At this time, his international fame was on the rise. Among the orchestras Bychkov was conducting were the Berlin Philharmonic and the Royal Concertgebouw Orchestra. He also signed a 10-year contract with Philips Classics Records, for which his recordings – with the Berlin Philharmonic – included Shostakovich’s Fifth Symphony.

After fifteen years in the USA he moved (with his second wife, the French pianist Marielle Labèque) to Paris. He also returned regularly – as a guest – to the Soviet Union and then to Russia and worked with the Saint Petersburg Philharmonic. In the late 1990s he became the chief conductor of the WDR Symphony Orchestra in Cologne. Exactly 30 years after the moment when, having just emigrated, he had been walking the streets of Vienna and eating bananas in the park, he was now conducting Wagner’s Lohengrin at the Vienna State Opera.

He left his post in Cologne in 2010 and began working as a freelancer. He had long since become one of the world’s top conductors, so he could choose his repertoire and which orchestras to work with. He was constantly turning down offers of positions as chief conductor, and he no longer wished to be tied down. That is, until the moment came in June 2017, after the last concert of the season, when a twenty-member delegation of players from the Czech Philharmonic approached him…

Prague, 2020

“What is it actually, that we do as musicians? We interpret music created by someone else. We are interpreters. Take someone like Daniel Day Lewis. He is completely different in every film. When he prepares himself for a role as a boxer, let’s say, he trains with a real boxer. When he was preparing for The Last of the Mohicans, he was living on a reservation with Indians, learning from them, almost becoming one of them. He does that with every role, and that’s why he is completely different in each one.

We have to do the same thing. But how when we can’t walk in the shoes of the composer? Through music we are also interpreting culture. The culture into which we were born. And in order to be able to do that, we can’t remain just tourists. We have to live the culture in question. Somehow, perhaps not every day, but we must live it. Otherwise, we would be limited just to that culture into which we were born, which would mean that I could only conduct Russian music. And I would never accept that.

When I want to conduct German music, I have to absorb the German mentality, body language, sense of humour… That doesn’t mean that I become a German. But I become more credible. You can’t leave your roots behind completely, no matter how much you might want to; genetics are just too strong. But we have to keep adding layer upon layer onto that foundation that we come from. We have to let our identity undergo an evolution.

And what has Czech identity given me? Not long ago, I told my colleagues at the Czech Philharmonic, “You know, I’m watching you. What you are like, and what makes you the way you are. What I see are very quiet, unpretentious people who are sincere, sensitive, and enormously musical. And who are extremely connected to the country where they were born.”

We’re playing Mahler. Everything that he wrote has to be interpreted as if with a magnifying glass. With him, seemingly tiny things are expanded a hundred times, and for you Czechs, that’s not completely natural. The Czech Philharmonic players can do it. They are such excellent musicians that they can do anything. One must adapt to what one happens to be playing. To become someone else, someone new each time you go outside of your own domestic territory…

Naturally, there is no such thing as an ideal, absolute interpretation. But there is one thing that is absolute: an authentic soul. When that is present, all differences are welcome. And when that is not present, it’s a waste of time.”

What a wonderful read. I am not sure if to feel inspired or to stop being a composer/producer/ keyboard player. These pro-conductors accomplished so much. I feel like ….Anyways, thank you for sharing this info. I enjoyed it.