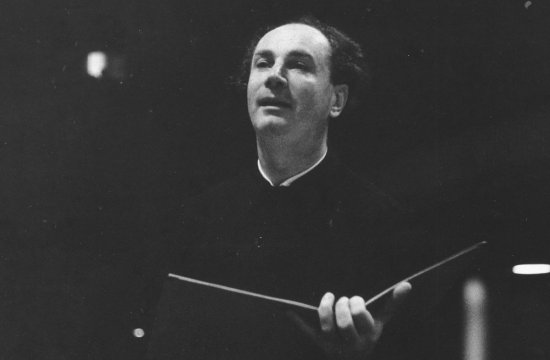

Many still remember his performance of Smetana’s Má vlast with the Czech Philharmonic at the opening concert of the 1990 Prague Spring Festival as one of the most powerful and symbolic musical experiences of the entire period following the Velvet Revolution, and rightly so. But might our recollections of that euphoric period be obscuring our view of Kubelík’s life as a whole? Are we keeping sufficiently in mind that the man who returned home in the spring of 1990 was not just an extraordinary artist, but also a person of enormous depth and moral integrity, as he demonstrated all his life? Are we keenly aware of how different things would have been if from 1948 to 1990 a man of Kubelík’s greatness had not been forced to live and breathe for this society and its culture only from afar? And are we well acquainted with everything that shaped Kubelík’s life and with the formative influence he had everywhere he was working before the euphoria of 1990?

Childhood with the Muses

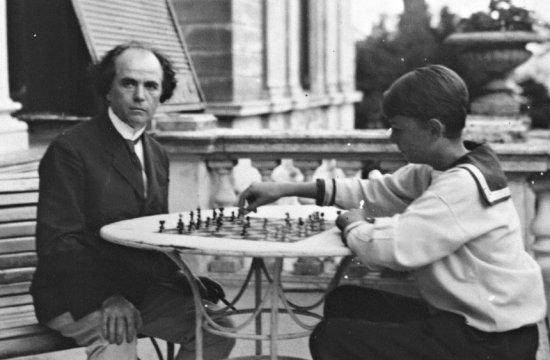

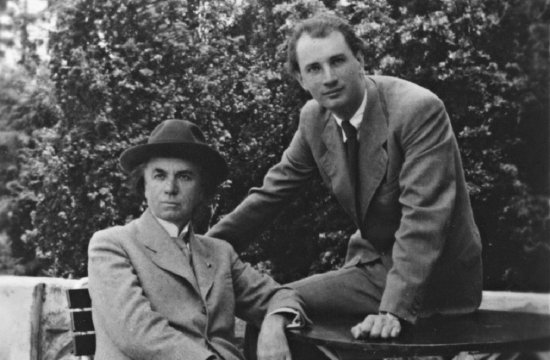

From childhood, Rafael Kubelík was surrounded by culture at the highest level. He was born on 29 June 1914 at the castle in Býchory near Kolín as the sixth of eight children of the famed Czech violinist Jan Kubelík and of the Hungarian countess Marianne Czaky-Szell. From his father, he learned not only the fundamentals of violin playing and music theory, but also something more: “Our family became poor in a relatively short time, so as a 16-year-old student I went through difficult times with my father, and financial difficulties in particular. That was not so important, however. What remained important to me was that my father, who had had to struggle against so many obstacles all his life (…), always remained a clear role model for me. He never ceased to show me what is important in the life of every artist. (…) There was a bit of genuine humanity in his world, giving his music making warmth and tradition that both found their source in the days when a spirit of humanism still existed.”

From 1929 to 1933, Rafael studied composition, violin, and conducting at the Prague Conservatoire. His violin teacher was Jindřich Feld, he was a composition pupil of Otakar Šín, and he learned conducting from Pavel Dědeček. He was also an outstanding pianist, and he accompanied his father in the 1930s on a concert tour of Romania, Italy, and the USA.

Successes and Deliberations

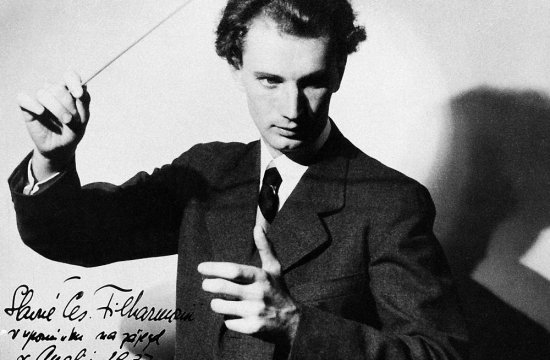

Kubelík conducted the Czech Philharmonic for the first time in January 1934. He was just 19 years old! And two years later he was a full-time conductor. In the autumn of 1937 he stood in for Václav Talich on a Czech Philharmonic tour of England, Scotland, and Belgium. His extraordinary talent and musicality won over both the public and the critics, who foresaw a brilliant future for him. This was probably understandable when the young Kubelík was riding a wave of tremendous triumphs, as is usual for young, successful conductors. However, when the 23-year-old artist was asked to discuss a tour, he did not fail to remember the teachings of his father or the values that he had learned from him: “As a small nation, we cannot be victorious abroad otherwise than by presenting ourselves to the world as a nation of high artistic culture. We can do so with a clear conscience. With our music, we can lay claim to one of the leading positions. It is our nation’s mission in the world to be bearers of culture.”

In August 1939, Kubelík was appointed to the helm of the Brno Provincial Theatre. Even under the difficult conditions of the Nazi occupation, in less than three complete seasons, he succeeded at programming works by Smetana, Dvořák, and Janáček as the core repertoire. However, he also prepared a production of Berlioz’s opera Les Troyens! The last two months of Kubelík’s tenure as chief conductor were marked by the 100th anniversary of Antonín Dvořák’s birth. His opera The Devil and Kate was the final work performed in November 1941 before the Nazis closed the theatre. Kubelík returned to Brno in 1947 to guest conduct the premiere of his own opera Veronika.

Chief Conductor of the Czech Philharmonic

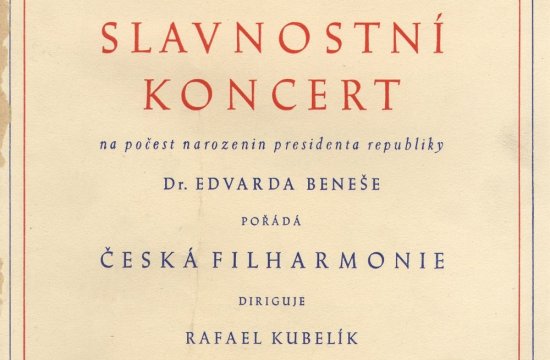

Rafael Kubelík served as the artistic director of the Czech Philharmonic from 1942. Although the programming had to conform with the limitations of the period, Talich’s 28-year-old successor devoted himself above all to works that fortified the people’s hope and faith. He conducted Novák’s Saint Wenceslas Triptych, Janáček’s Taras Bulba, and Smetana’s Má vlast over and over. The latter work was heard symbolically in liberated Czechoslovakia on Prague’s Old Town Square on 20 June 1945 at a “Concert of Thanksgiving”.

Kubelík then formulated a new line of programming for the orchestra with the goal of “repaying an incurred debt” to Russian, French, and Anglo-American music, but at the same time focusing on Czech works. To manage all of that, Kubelík was “forced” to establish the Prague Spring International Music Festival, which took place for the first time in May 1946. The return of the Rudolfinum to the Czech Philharmonic and the orchestra’s nationalisation in October 1945 were also thanks to Kubelík. He conducted the Czech Philharmonic for the last time for many years on 5 July 1948. He made the decision to leave Czechoslovakia, which was being taken over by a communist dictatorship. He never returned home from the concerts at the Edinburgh Festival.

Chicago and London

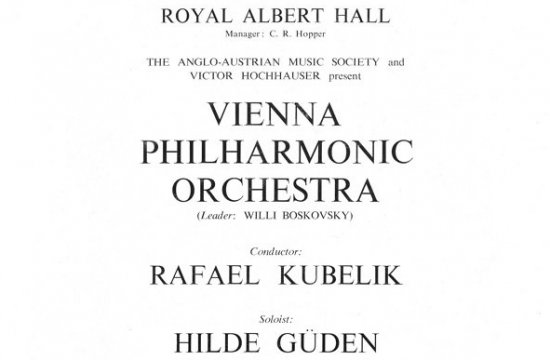

After going into exile, Kubelík guest conducted in the United Kingdom and the Netherlands, and in 1949 he set out on a concert tour of Australia. On 17 November of that year, he made his debut with the Chicago Symphony Orchestra. He was such a success that he was made the orchestra’s music director for three years beginning in September 1950. Typically for Kubelík, the programming included encounters between music of the 20th century, works by Czech composers, and the worldwide repertoire in all of its breadth. Compositions by Bartók, Poulenc, Copland, and Harris appeared on programmes; Czech music included not only Dvořák and Smetana, but also Janáček, Suk, and Martinů. A concert performance of Wagner’s Parsifal in April 1953 was like a premonition of the next stage in Kubelík’s life.

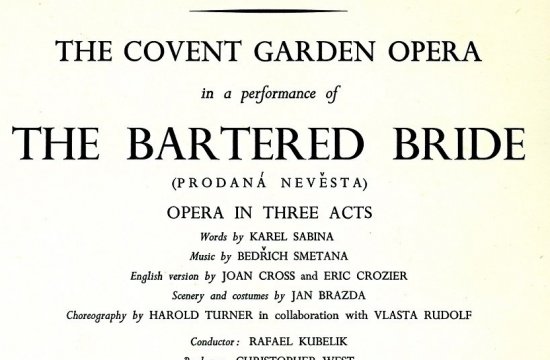

From 1955 to 1958 he served as music director at London’s Royal Opera in Covent Garden. And what did he try to do? He wanted a world without prima donnas: to form a permanent, high-quality British artistic ensemble. However, he was heavily criticised for this, and especially by the British… While at Covent Garden he managed to perform Berlioz’s opera Les Troyens again and to perform a great deal of Czech music, including Jenůfa and The Bartered Bride.

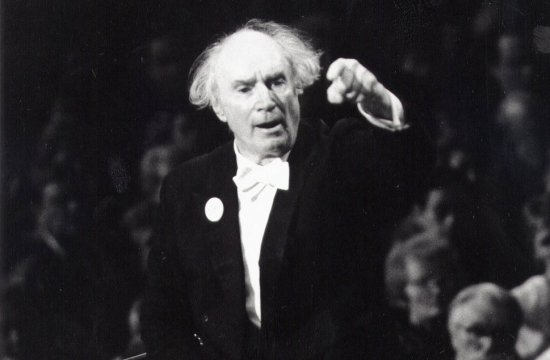

I Am Number 115

The legendary Kubelík era. That is the description for the 18 years (1961–1979) when he was the chief conductor of the Bavarian Radio Symphony Orchestra. There was great understanding between the orchestra and its conductor, and Kubelík elevated the ensemble to world class standards, not as a conductor-dictator, but as a conductor-democrat: “I can’t give the orchestra advice while being undisciplined myself, acting like a prima donna, and letting less than ideal circumstances upset me. I am number 115 in front of the orchestra’s 114 players.”

He enriched the repertoire with works by Czech composers and again paid great attention to music of the 20th century (often performing compositions by K. A. Hartmann). He took the orchestra on tours of Europe, the USA, and Japan, and he made a large quantity of LP recordings; his first complete set of Mahler symphony recordings became especially famous. He continued to guest conduct the Bavarian orchestra until 1985, when health problems forced him to retire.

Kubelík was a world famous, sought-after conductor. Besides tenures at the helm in Chicago, London, and Munich and a brief stint at New York’s Metropolitan Opera, he also guest conducted top orchestras everywhere, giving concerts in Berlin, Vienna, London, Stockholm, and Amsterdam. He conducted regularly in New York, Boston, and Cleveland, and he returned to Chicago in the middle of the 1960s. His appearances in Israel and Australia were highly acclaimed. And added to that was his work in the field of opera. Kubelík said a good symphonic conductor must have operatic experience and vice versa. He led many operatic productions in Munich, Hamburg, Vienna, Milan, and even San Francisco.

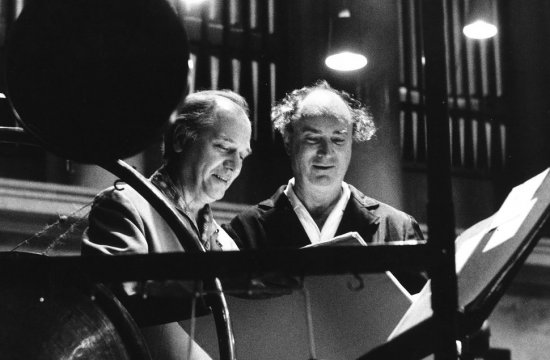

In the Recording Studios

There are audio recordings capturing Kubelík’s entire conducting career, beginning with pre-war recordings with the Czech Philharmonic and continuing with a rich discography spanning from 1948 to 1985 and on to the last recordings, again with the Czech Philharmonic, from the early 1990s. When making recordings, he tried to avoid chopping compositions into small sections. He always strove for the music as a whole to “breathe” (as he put it) as much as possible.

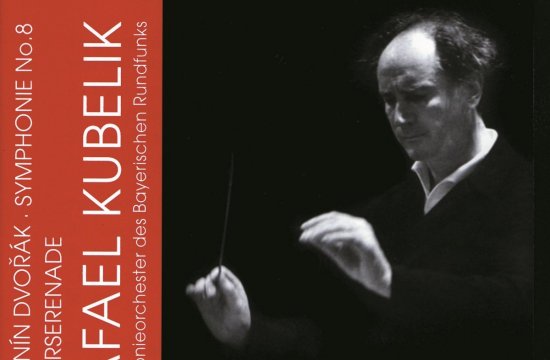

The bulk of Kubelík’s recordings cover music of the 19th century, symbolised by the complete symphonies of Beethoven, Schumann, Brahms, and Mahler. His recordings of 20th-century music include works by Orff, Hindemith, and Schoenberg. Czech music holds a place of importance, including all of Dvořák’s symphonies with the Berlin Philharmonic and six complete recordings of Smetana’s Má vlast made in Chicago, Vienna, Boston, Rome, Munich, and finally in Prague with the Czech Philharmonic.

A Freedom-Loving Czechoslovak

Kubelík’s departure into exile after the communist putsch caused him many difficulties, but the decision was clear. “I left so I would not have to collaborate in liquidating our culture and our humanity. But I never ceased to believe in the law of the triumph of truth, of that which is right.” From the beginning of the 1950s, he received invitations to return to Czechoslovakia. He repeatedly answered that he would return gladly, but under the condition that “every decent Czech and Slovak, with talent or without, must have freedom of belief, freedom of creation, freedom of expression, and freedom of movement.”

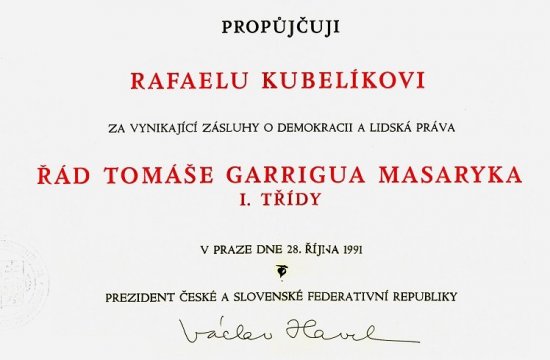

After the occupation of Czechoslovakia in August 1968, he organised a boycott of Warsaw Pact countries by the artistic elites of the day. Among the more than 100 artists who supported Kubelík’s protest were such figures as Rudolf Firkušný, Igor Stravinsky, and Daniel Barenboim. In July 1979, Kubelík joined with the violinist Yehudi Menuhin in writing a letter to the Soviet leader Leonid Brezhnev, asking him to use his power to urge the Czechoslovak government to free Václav Havel and other imprisoned signatories of Charter 77.

“I have passionately awaited this moment, and I believed it would come one day. I am grateful to God, the whole nation, my friends, and all of you.” Those were Kubelík’s first words upon returning to this homeland on 8 April 1990. Then a month later, on 12 May, the “harps of the prophets” that begin Má vlast were heard under Kubelík’s baton. Just like 45 years earlier after the end of the war, he also conducted Smetana’s symphonic cycle on Old Town Square. The “Concert of Mutual Understanding” took place on the day of the first free election, 9 June 1990. In October 1991 he appeared on stage together with the Czech Philharmonic and Rudolf Firkušný, and one critic wrote: “Together, the age of the evening’s two protagonists is well in excess of a century and a half, but their artistry is supremely youthful, brilliant, and robust.”

Rafael Kubelík bade farewell to conducting definitively in November 1991 on a Czech Philharmonic tour of Japan. Má vlast was on the programme. He died on 11 August 1996 in Kastanienbaum, Switzerland.

After the 1990 Prague Spring Festival concerts, at the end of July he wrote to his “rediscovered” Czech Philharmonic colleagues: “Dear Friends, I am still in Prague—at home—in my thoughts! I thank you with all my heart for all of the beautiful music, faithfulness, and love that you gave me so generously! I wish you good health and strength—for the wellbeing of our music! I embrace your most cordially. Yours sincerely, Rafael Kubelík”.