The “childlike and fairytale” elements of the Fourth Symphony are “in the DNA of the orchestra” says Bychkov. “It’s in their soul.” The sleigh bells that Mahler later claimed to be represent the bells on a fool’s cap arrive as irony or mockery but are transformed into the laughter of angels in the final movement. As listeners we are invited to fill our lungs with the scent of the forest, to dip our fingers into freshwater streams, to smile at the trill of birdsong, to be startled by the music of an itinerant fiddle player, to feel at peace with the natural world, to think, to feel, to imagine, to transcend.

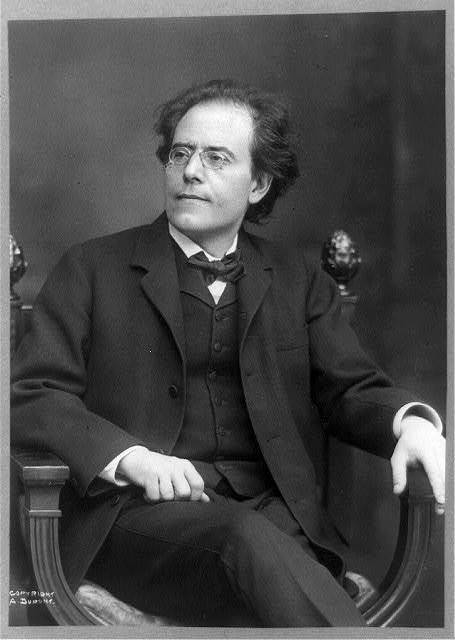

These are themes that can be discerned throughout the music for voices and orchestra that Gustav Mahler, a German-speaking Jew and Bohemian subject of the Austro-Hungarian Empire, wrote across the twenty-two years in which he became renowned as a conductor from Moscow to New York but was dismissed, misunderstood and even reviled as a composer. From the pastoral soundworld of the Fourth Symphony we can appreciate more keenly the audacious counterpoint of heroic and demotic music in Mahler’s First Symphony, the triumphant passion of the Second, the long love-music of the Fifth and the immense sorrow of the Ninth.

These are themes that can be discerned throughout the music for voices and orchestra that Gustav Mahler, a German-speaking Jew and Bohemian subject of the Austro-Hungarian Empire, wrote across the twenty-two years in which he became renowned as a conductor from Moscow to New York but was dismissed, misunderstood and even reviled as a composer. From the pastoral soundworld of the Fourth Symphony we can appreciate more keenly the audacious counterpoint of heroic and demotic music in Mahler’s First Symphony, the triumphant passion of the Second, the long love-music of the Fifth and the immense sorrow of the Ninth.

To engage upon a complete cycle of Mahler’s symphonies is an act of profound commitment between an orchestra, a conductor and their audience. Here we have the polyphony of life, rural and urban, benign and malign, and a world view that extends from the intimate to the infinite. With the possible exception of Beethoven’s symphonies, no other body of work is as philosophically ambitious in its scope.

Within a few minutes of Bychkov’s first rehearsal with the Czech Philharmonic of Mahler’s Second Symphony, ‘Resurrection’, Bychkov says that he “knew immediately that it was theirs. I felt it in their sound and in the way they were responding to the dynamics.” How would he describe that sound? “It’s enormous warmth, a very distinct string sound, a very distinct woodwind sound. I always say that the most important thing for us is to remain different. Being different is so vital in the world, where everything is more and more homogeneous. And music needs it.” Particularly the music of Mahler, which is both the music of a polyglot society and the music of a volatile and solitary genius.

“It’s about our nervous system responding to a work of art, in this case a piece of music, the same way that a nervous system of one individual will respond to meeting another individual,” says Bychkov. “We understand nothing but we feel something. We are touched by something without knowing why. And when we are touched we want to hear it again, and eventually we’d like to know what makes it so touching, what the story is telling you, and you start imagining and from there the life of the piece and our life with it.”

As a practical musician, Mahler gives more precise and exacting indications of dynamics, tempo, mood and articulation in his scores than any other composer of his era. Repeated figures that you might expect to be played identically at each iteration are disrupted and developed by different emphases, particularly in Totenfeier, the first movement of the Second Symphony, which was written in Prague in 1888. Minute syncopations between different instrumental groups are not mere details but essential to the character of a moment and thereby impact on the moment that follows. “We can never know enough,” says Bychkov, “the more we do, the more we think.”

Silence, upon which only the finest thread of sound can be placed with utmost care, is as intrinsic to Mahler’s music as the shattering tutti climaxes of joy or anguish with which we associate his symphonic writing. The manifold, almost neurotically detailed, directions that he left in his scores for those who would interpret his music run out by the time of the Ninth Symphony, a work that he did not live long enough to hear played or to conduct himself. When you consider that the harmonics that open the first movement of the First Symphony were introduced by Mahler only in rehearsal, it is daunting to imagine how he might have revised his last complete work had he lived longer.

Bychkov, whose role in this work is to sustain and nurture a structure that is both huge and incredibly delicate, maintains that there is grace and peace in the Ninth Symphony. But the overriding impression is of utter solitude and sometimes desolation. While the Ländler of the second movement revisits the many rustic dances of Mahler’s earlier works, the Rondo burleske takes the form of a Totentanz in which high- and low-born must all face judgment. Minuscule adjustments of tempo have a dramatic effect on the character of these dances, and therefore on the longer movements that frame them.